-

-

-

Tổng tiền thanh toán:

-

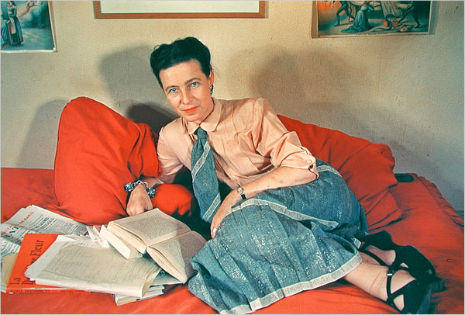

Simone de Beauvoir

20/04/2019

Simone de Beauvoir was probably best known as a novelist, and a feminist thinker and writer, but she was also an existentialist philosopher in her own right and, like her lover Sartre, thought a lot about the human struggle to be free.

Beauvoir’s most famous work was The Second Sex from 1949, a hugely influential book which laid the groundwork for second-wave feminism. Where first-wave feminism was concerned with women’s suffrage and property rights, the second wave broadened these concerns to include sexuality, family, the workplace, reproductive rights, and so on. All that started with Beauvoir’s The Second Sex, where Beauvoir outlines the ways in which woman is perceived as “other” in a patriarchal society, second to man, which is considered—and treated as—the “first” or default sex.

One of the most famous lines from that work is: “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.” Beauvoir means by this is that the roles we associate with women are not given to them in birth, by virtue of their biology, but rather are socially constructed. Women are taught what they’re supposed to be in life, what kind of roles they can or can’t perform in virtue of being of "the second sex." Today we might express this idea using the distinction between sex and gender, where one’s sex is just a biological fact, but one’s gender identity is socially constructed. In 1949, this was a truly radical idea.

So how does this idea relate to existentialist concerns about freedom? One of the main questions existentialists worry about is how to achieve “radical freedom,” or the kind of freedom that comes from making decisions in what Sartre called “good faith.” These are the decisions that come from and express an authentic self. If someone is living in “bad faith,” they allow themselves to be ruled by identities imposed on them from the outside. Their decisions do not reflect who they truly are.

It makes sense, then, that if someone is taught her entire life that to be a woman, she must look a certain way, act a certain way, play a subservient role within her family, and work only certain kinds of jobs, it is going to affect her sense of freedom and authenticity. Being seen—and seeing yourself—as “the second sex” certainly seems to complicate the question of how to achieve this radical freedom existentialists worried about. Indeed, it makes the struggle to achieve this kind of freedom sound like a white male problem, something you have to be in a privileged position to even think about at all.

Although third-wave feminism often critiques second-wave feminism for its focus on the struggles of white middle-class women, ignoring the plight of women of color, poor women, women in the developing world, disabled women, etc., Beauvoir’s insight about the experience of being a woman in a patriarchal world can naturally be extended to include the experience of being black in a white world, or being “other” in any world where you’re constantly taught that you’re second class. That’s going to shape what you think your life choices are—it’s going to change how you perceive your own freedom.

If we’re going to talk about “radical freedom” at all, then it should be in the context of the real-life choices we are presented with in our lived experiences. It can’t be an abstract choice to be free. This was one of Beauvoir’s biggest insights.

Simone de Beauvoir (1908-1986)

Các tin khác

- Sách Ngoại Văn - BOA Bookstore 01/06/2019

- BOA Bookstore (Vietnam) shortlisted for LBF International Excellence Awards 26/03/2019

- Văn hoá đọc sách tại TP. Hồ Chí Minh 28/02/2018

- Fostering A Culture Of Reading In Saigon Today By Lilly Pugh 28/02/2018

- 12 cool indie bookstores in Asia every bibliophile should visit 28/02/2018

- Saigoneer’s Picks: 10 Places to Buy Artsy Gifts in Vietnam 26/02/2018

- English language books in Ho Chi Minh City 23/02/2018